Do You Want a Puppy?

To reach Muslim neighbors and remove barriers to the gospel, a worker family uses contextual language and lifestyle to connect.

By Anita Rahma

My family and I have been making our home in a primarily Muslim slum community on the outskirts of Jakarta for over the past decade. We believe that the Lord has planted us in this place and that God deeply loves the people here. We try to be witnesses to the gospel in word and deed, sharing about Christ in contextually appropriate ways. This has certainly not been an easy journey, and we continue to learn as we go along.

One afternoon recently, my son and I were biking to the photocopy store, when we passed a house with adorable little puppies on the front porch. After completing our errand, we went back to ask if we could hold the puppies. We knew the son of this Christian family, and the grandmother graciously welcomed us in and indulged our puppy-holding desires. She told us in a few weeks they would be for sale, at the cheap price of $3.25 each.

My son named the puppy he was holding “Oreo,” and immediately started making plans to purchase the puppy with his allowance. I had to explain to him, once again, that we could not have a dog. “We are trying to show God’s love to our neighbors in this place,” I said. “Our Muslim friends are terrified of dogs. We cannot have a dog.”

When we say “yes” to God’s call in our lives, it often means saying “no” to many other things—often good things. For us, saying “yes” to trying to communicate the gospel in this place means surrendering some things that we might feel like we have a “right” to.

We choose to not have a dog. We choose to not eat pork. We choose to not drink alcohol. We choose to wear clothing that is respectful and appropriate. And those are the easy, superficial things. But we do not want these essentially unimportant things to be stumbling blocks to our Muslim neighbors. We do not want the trappings of “Christianese” language or culture to be walls keeping our friends from being able to really hear the good news of Jesus.

Even though we live among two of the largest unreached people groups in the world (Sundanese and Java Pesisir), as we serve here, we learn that many people have already had interactions with Christians in the past. And very frequently, there have been negative experiences—even traumatic and manipulative. When we have built enough trust in relationships for people to share such things, we are indeed treading on holy ground.

We run a free school in our neighborhood, tangibly sharing God’s love with our students and their families. We desire to give them hope for a better future, equipping children to read well and get off to a good start in elementary school. Through this school, doors have opened over the years to know hundreds of families. We have shared stories from scripture, prayed for people when they are sick or demon possessed, and been part of life in the community. It has been beautiful and ugly, heartwarming and heartbreaking— a sacred journey.

Reaching unreached people groups demands more than what is easy or comfortable.

We chose from the beginning of our work here to use contextual language. (There are many insightful books that discuss this topic, and it is beyond the scope of this article.) We say we are followers of Isa Al Masih. We learn to pray with our eyes open and our hands lifted up. We do not have any crosses or pictures of Jesus and his disciples displayed in our living room (we do, however, have one cross and one picture of Jesus in our bedroom).

Again, we are trying to get rid of as many barriers to the gospel that we can. This is not because we are ashamed of the gospel or trying to hide it, but because we want our neighbors to meet Jesus. We want them to learn about Jesus, not as a Western, outside religion, but as a Savior who has come to announce his loving kingdom to them.

This is not easy work. The more we learn, the more we know we have more to learn. We sow seeds. We trust God to bring the growth.

There is pushback from Christians who do not understand. It is easy to own a dog, eat pork, flaunt Christian terms for God in drive-by evangelism encounters and then hope Muslims respond. It is more comfortable to gather with other believers and talk about religious things with terms we grew up knowing and understanding.

Reaching unreached people groups demands more than what is easy or comfortable. God invites us to surrender. To learn His ways are not our ways. To confess that we continue to have much to learn, and that much has been done in the name of Christ that is counter to his way. While on furlough last year, we sat and listened to seasoned missionaries share about a movement of people coming to know Christ in their context. We saw photos of baptisms and listened to testimonies of changed lives.

I cried as I listened, wrestling with God. Are we doing something wrong? Or is God trusting us with this journey of not-yet-seeing-fruit? I think the answer is the latter, but as we continue to serve—longing for the day when people will decide to follow Christ—it can feel like a lonely journey.

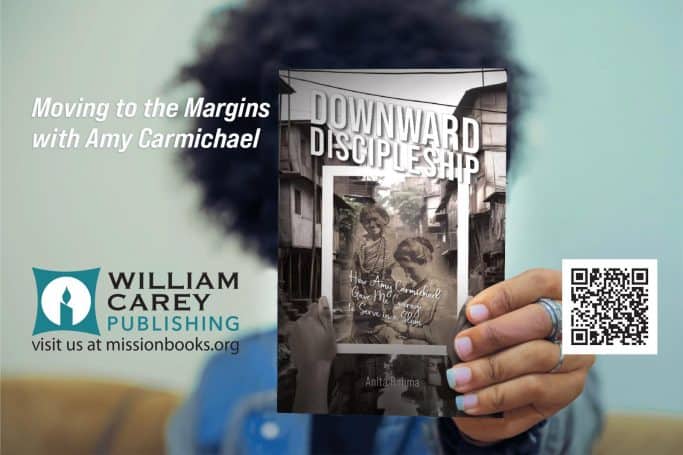

In my new book, Downward Discipleship: How Amy Carmichael Gave Me Courage to Serve in a Slum, I share seven invitations that I have learned from the life and legacy of missionary Amy Carmichael. Amy served for over fifty years in India, founding the Dohnavur community and rescuing girls from lives of temple prostitution. I weave in stories from our context of ministry in Indonesia, and reflect on how Amy has inspired me to carry on— even when it is hard.

Our hope is that those who hear our story will be inspired to thoughtfully discern how to choose a life of downward discipleship wherever God might be leading. Moving from self to surrender, and control to compassion—may the Lord lead us all to humble lives of serving and witnessing to our King.