Ambassadors to the Unreached

Does the Unreached People Group framework still serve as a helpful lens as we look to the future of mission?

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Lausanne Congress, a global missions gathering at which missiologist Ralph Winter introduced the Unreached People Group (UPG) framework for thinking about Jesus’ commission to his followers: “Go and make disciples of all peoples.”

In September, the fourth Lausanne Congress on World Evangelism will gather 10,000 in-person participants from the global church in South Korea and thousands more through virtual venues to consider gaps and opportunities that remain in this call of Jesus. In an increasingly interconnected world marked by transnational migration, does the UPG framework still serve as a helpful lens as we look ahead to the next decade of mission?

Several years after the first Lausanne gathering in 1974, a strategy group offered further definition to the UPG framework. A people group, they proposed, is “the largest group within which the gospel can spread as a church planting movement without encountering barriers of understanding or acceptance.” Followers of Jesus within such a group can communicate freely without significant cultural differences that could threaten gospel sharing.

A group that is “unreached” refers to one that has 5% or fewer professing Christians (those who claim Christian identity, often because of cultural heritage but not necessarily because of personal conviction) and 2% or fewer of practicing Christians (those who see themselves as disciples of Jesus who seek to make disciples). A subset of UPGs, “unengaged people groups,” describes groups who have no known Christian presence among them.

What does this practically look like in many places around the world?

Imagine you live in a town of 10,000 people that meets this criteria of “unreached.” There might be 200 residents in your town who have “Christian” on their government-issued identity card. There is one public place of worship in the town for these Christians, and of these 200, 30 attend gatherings for worship and prayer on a weekly basis.

If you happen to meet one of these people at your place of work or in your neighborhood, you most likely won’t know that they are Christian. There are also perhaps 20 evangelical Christians in your town, but they do not have a visible gathering place because they are not part of an officially recognized religious group, so you won’t ever see them gathering as the body of Christ.

If you happen to live near one of these followers of Jesus or work in the same factory, she may share stories about Jesus as you get to know each other better. One of these believers may offer to pray with you for peace and healing in the sickness you’re experiencing. But because many of these believers are the opposite sex from you, and cultural norms in your town discourage having conversation with unrelated people across these boundaries, it’s even less likely that you’ll ever meet one of these followers of Jesus. Furthermore, these believers won’t likely share the good news across your town of 10,000, much less across your people group of 2 million spread across a large area in your country.

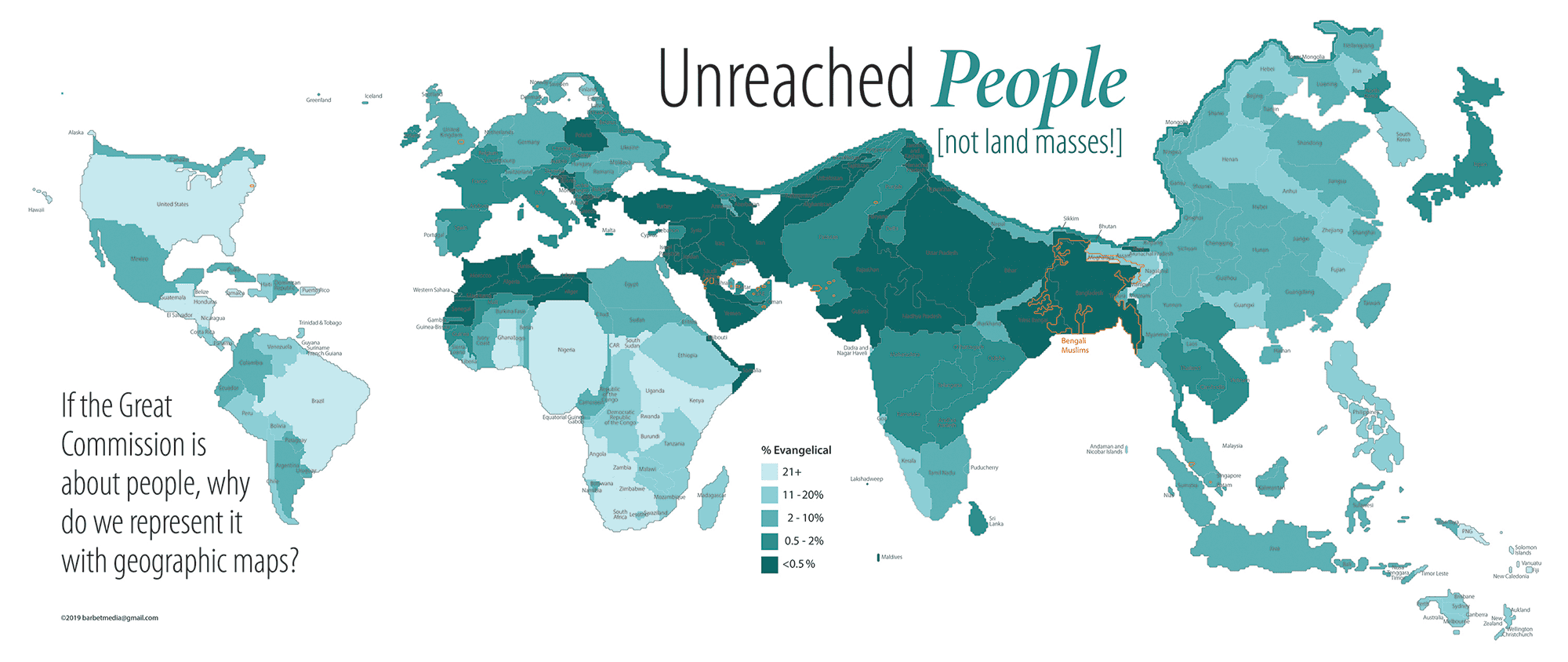

This example highlights the continuing need for cross-cultural ambassadors to go with the good news to the approximately 7,000 remaining UPGs, most of whom live in the 67 countries of the 10/40 Window, a swath of the globe stretching from North Africa in the west to Japan in the east.

A focus on people groups shaped by language and cultural norms invites us to remember that God, the pioneer and primary actor of mission, chose to work through incarnation.

Focus on UPGs has galvanized interest, research and knowledge of peoples among evangelical Christians around the world like perhaps no other single lens in my lifetime. In the 1980s and early ‘90s, mission organizations and churches learned about people groups that would likely never have the opportunity to hear the gospel unless someone crossed barriers of understanding and acceptance. Christians began to pray for people groups in distant places. Some found ways to visit these locations in order to develop relational ties or send long-term workers. Some developed friendships with neighbors from UPGs much closer to home.

VMMissions increasingly partners with churches in the global south, the majority Christian world, as they send workers to live and work among UPGs as ambassadors of the gospel. Many of these sent ones continue to work in the professions they practiced in their passport nations.

Last fall, I joined an annual gathering of Anabaptist sending organizations, most of whom were from the global church. Members of that group are near-neighbors to half of the remaining UPGs, living in the same country or an adjacent one and often sharing more cultural similarities to these UPGs than do many Western Christians. Surely one important piece of completing the commission of Jesus is greater collaboration as his global body in sending workers into new fields.

Jesus came as a baby to a particular people shaped by language and culture. He learned language and proclaimed the gospel of the kingdom from within a culture. And just as Jesus crossed barriers of understanding and acceptance, he invites his followers to do the same. After receiving the promised Holy Spirit, the disciples would be witnesses of the gospel in four categories of places: Jerusalem, Judea, Samaria and the ends of the earth (Acts 1:8). None of these represented home for Jesus’ listeners that day, most of whom were Galileans.

This work remains unfinished by Jesus’ own criteria. Jesus said, “[T]his gospel of the kingdom will be preached in the whole world as a testimony to all nations, and then the end will come” (Matt. 24:12-14). Let’s intentionally live toward the day when we’ll join “a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language” (Rev. 7:9) in worship around the throne of the crucified Lamb.